October 16, 2015

Story by Greg Harris

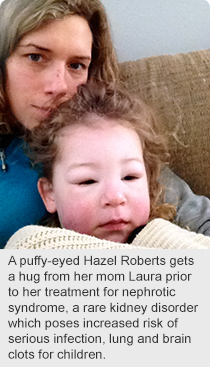

CALGARY — Laura Roberts and her husband Adam first suspected their daughter Hazel might have a health problem when she started waking up with puffy eyes.

“At first, the family doctor thought it might be an allergy,” says Laura. “We changed her bedding, changed the detergent we were using and started giving her Benadryl,” an over-the-counter anti-allergy medication.

But Hazel’s condition worsened. Then two-years-old and living in Fort McMurray, she wound up undergoing treatment in hospital for a rare childhood kidney disorder called nephrotic syndrome.

But Hazel’s condition worsened. Then two-years-old and living in Fort McMurray, she wound up undergoing treatment in hospital for a rare childhood kidney disorder called nephrotic syndrome.

Today, Hazel is five-years-old, doing well, and one of the first children to be enrolled in a national study which aims to identify best practices in treating nephrotic syndrome, a condition in which blood protein ends up in the urine.

According to Dr. Susan Samuel, the Calgary-based Alberta Health Services pediatric nephrologist who leads the study, Hazel’s story is not uncommon.

“Nephrotic syndrome is not seen very often by family practitioners,” she says. “There are only about 100 cases in southern Alberta.”

Prompt recognition and management of the condition is important since children can also get very sick with infection, and can also have clots in their brain or lungs while they are leaking protein into their urine.

Because it’s seen so rarely, it’s also a challenge to generate high-quality research evidence about it. There are very few studies that involve significant numbers of children.

In the recently launched research study, nephrologists at 13 pediatric centres across Canada will pool information on their patients’ responses to treatment. When the five-year project is complete, it’s expected the patient registry and data repository will have information on more than 600 cases.

Steroids have been the standard treatment for nephrotic syndrome since the 1950s, but there is wide variation in the total dose and duration of therapy prescribed for relapses of nephrotic syndrome. Variations in the length of treatment range from six weeks to six months.

“Steroid treatment can have negative side effects, such as obesity, slowed growth, high blood pressure, cataracts, poor bone health and behavioural issues,” says Dr. Samuel.

“One potential benefit of the study would be to determine the minimal amount of steroids that can be prescribed while still remaining effective in preventing relapses of disease,” she adds.

Researchers also hope the findings will lead to the development of targeted therapies in their patients, as well as help doctors predict the course and severity of illness in their patients.

The cause of childhood nephrotic syndrome is unknown and there is no cure. Many children eventually outgrow the condition, but others stay in a cycle of relapse and remission and must undergo a course of steroid treatment every few months. Some even progress to have kidney failure and require dialysis or kidney transplant.

The study is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Kidney Foundation of Canada. To date, more than 150 patients have enrolled.