February 25, 2021

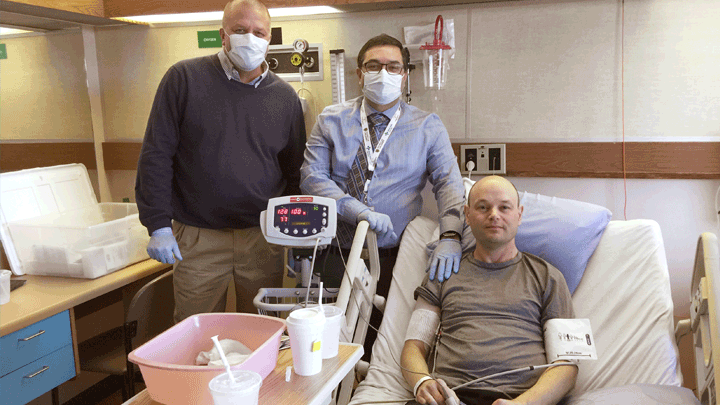

This photo, taken in 2017, shows study participant Darren Bidulka shortly after he received a transfusion of his modified stem cells. He’s shown here with research doctors Jeffrey Medin, left, and Aneal Khan. Photo supplied.

Story by Greg Harris

When Darren Bidulka agreed to try an experimental gene therapy in Calgary in 2017 to treat his rare, life-shortening illness, he was cautiously optimistic, but wasn’t going to pin all his hopes on it.

His condition, Fabry disease, can damage major organs and shorten lives. It is currently treated with intravenous enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) every two weeks, which limits the impact of the illness.

But now, thanks to the gene therapy he received at Foothills Medical Centre (FMC), the 52-year-old no longer requires ERT.

“I’m really happy that this worked,” Bidulka says. “I can lead a more normal life now, without scheduling enzyme therapy every two weeks. I consider this a great success.”

The journal Nature Communications published results on Feb. 25 of the world-first, multi-centre Canadian trial.

Lead author of the paper, Dr. Aneal Khan, is also the Alberta Health Services (AHS) medical geneticist who led the experimental trial in Calgary.

“To date, we can say that the gene therapy has either partially or fully restored enzyme levels to a point where they are no longer considered deficient,” says Dr. Khan, also a member of the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary.

“These results show that just one treatment of gene therapy was enough to benefit patients. Now we need to see whether this single dose can last for the long term.”

People with Fabry disease have a gene called GLA that does not function correctly. As a result, their bodies are unable to make the correct version of an enzyme that breaks down a fat. A buildup of that fat can lead to problems in the kidneys, heart and brain. Untreated, men have an average lifespan of 58 years, and women, 75 years.

In total, five men participated in the study and were treated at FMC in Calgary, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, and the Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre in Halifax.

As a result of the gene therapy, all patients began producing the corrected version of the enzyme to near normal levels within one week. With these initial results, all five patients are approved by Health Canada to stop their intravenous enzyme therapy. So far, three patients have chosen to do so — including Bidulka — and are stable.

Dr. Jeffrey Medin, who is now the MACC Fund Professor at the Medical College of Wisconsin and Affiliate Scientist, University Health Network, Toronto, pioneered the treatment while he was a Senior Scientist at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto.

“After 20 years of working on this treatment, to see that patients could end up making their own enzyme, and that the treatment effect was sustained, is satisfying. We are elated!” Dr. Medin says.

For the study, researchers collected a quantity of each Fabry patient’s own blood stem cells, then used a specially engineered virus to inject those cells with copies of the fully functional gene that is responsible for the enzyme. The modified stem cells were then transplanted back into each patient.

The treatment, which was approved by Health Canada for experimental purposes, was the first trial in Canada to use a lentivirus in gene therapy. In this case, the specially modified virus was created at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, stripped of its disease-causing capability and augmented with a working copy of the gene that’s responsible for the missing enzyme.

Khan notes that the Calgary arm of the clinical trial was a team effort and wouldn’t have succeeded without the critical support of many people, including Shelly Jelinski, clinical research coordinator at Alberta Children’s Hospital, Dr. Ahsan Chaudhry, an oncologist with the Alberta Blood and Marrow Transplant Program, Nicole Prokopishyn, director of the Cellular Therapy Lab, Alberta Precision Laboratories, and hematologists Dr. Peter Duggan, Dr. Andrew Daly and Dr. John Klassen.

“The contributions of so many people in Calgary were instrumental for the success of this trial,” Dr. Khan says. “Everyone played a part, including AHS and the U of C. This shows the transformational power of doing clinical trials and the importance of research.”

The research team will continue to monitor each patient for five or more years from the time they received back their modified blood stem cells. Clinicians emphasize it will take many years of further testing before this experimental treatment becomes a clinically available standard of care.

An estimated one person in 40,000 to 60,000 has Fabry disease. There are about 500 people in Canada known to have this illness, although exact numbers are not certain due to the difficulty in identifying all those with the disease.

“This research is also incredibly important for many patients all over the world, who will benefit from these findings,” adds Bidulka, who now lives in Vancouver. “What an amazing result and an utterly fascinating experience.”