June 24, 2022

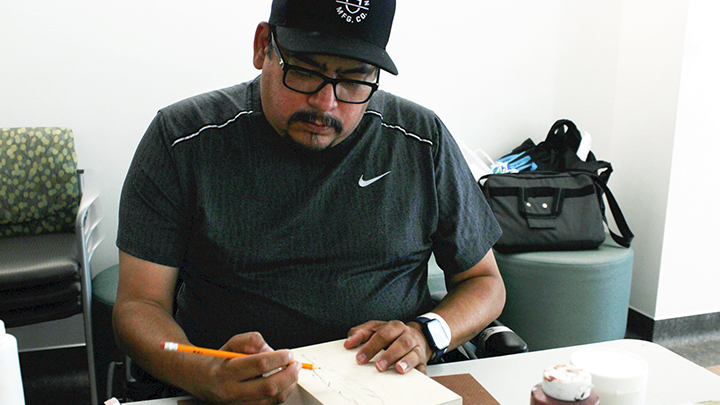

Steven Healy works on a smudge box on his final day of treatment at Chinook Regional Hospital, as part of the Spirit of Art and Reconciliation (SOAR) program. Photo by Patrick Burles.

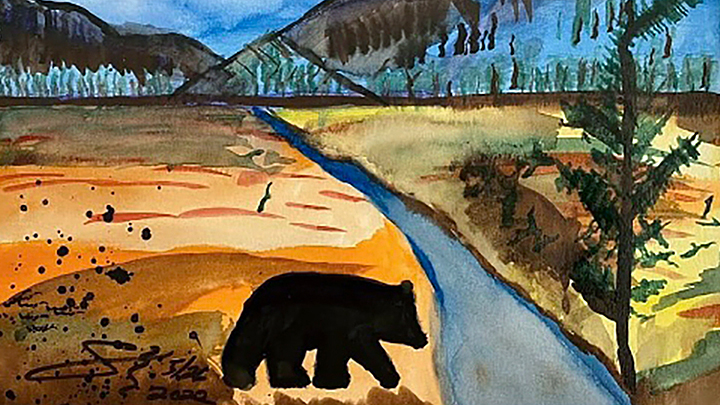

Black Bear is Steven Healy’s first project in the SOAR program. Photo supplied.

Story & Photo by Patrick Burles

LETHBRIDGE — It started with that stomach-turning feeling — your arms are full as you walk down a flight of stairs, when your foot comes down just a little wrong on the next step.

For Steven Healy, the ensuing fall brought his 220-pound frame crashing down on his right leg, snapping his tibia in two places. Fortunately, his phone was close enough for the voice-command feature to pick up his calls for help and dial 911.

Paramedics transferred Healy to Chinook Regional Hospital in Lethbridge where he would undergo surgery to realign the bones, followed by weeks of physiotherapy as an inpatient.

It was during his lengthy stay that Healy accepted an invitation to join the Spirit of Art and Reconciliation (SOAR) program. This joint initiative of the Indigenous Wellness Core and Therapeutic Recreation provides a mixture of traditional and Indigenous art projects.

"I was initially skeptical. To be honest, I thought it might be a waste of my time," he says, adding with a laugh that the height of his artistic experience was finger-painting as a child.

"Ultimately, I decided to go with an open but nervous mind."

It’s a common sentiment among newcomers to the program, says recreation therapist Michelle May. Once they get going though, she often sees the same positive result.

"Most clients come in saying, ‘I’m not an artist, this is going to be awful’, and they leave so proud of their work. We always frame their artwork at the end — and we’ve had people sometimes get really emotional and cry.

"At the end of the session, it looks like a weight has been lifted. You can see it on their face, you can see it in their body language," she adds.

Healy agrees, noting one of the benefits that surprised him most.

"I hadn’t taken my pain medication prior to one of the sessions, so my pain was high and becoming disruptive," says Healy. "Once I started painting, my mind was flooded with ideas and motivation — and I just forgot about my pain."

Where the program truly stands out is in the connections it helps patients forge. While designed with Indigenous patients in mind, it’s open to everyone, offering an opportunity for non-Indigenous patients to join the journey toward reconciliation and learn more about the peoples and culture that are native to this land. May noted that the benefits extend to staff as well, fondly recalling a patient who taught them a new Blackfoot word at each session.

It’s the connection that also stands out for Healy, who freely admits that he broke down crying during a smudge and prayer ceremony in his first session.

"Through this, I also got to meet another person that I share common ground with — being in a day school and residential school," he says.

"It was good to talk about that. There’s some pent-up anger. It was good to release that by talking to someone who went through the same thing.

"This whole program has been a powerful experience."