June 12, 2025

Members of the original Edmonton Protocol team a quarter-century ago included (rear, from left) Greg Korbutt, Eddie Ryan and James Shapiro and (front, from left) Jonathan Lakey and Ray Rajotte. Photo courtesy of Richard Siemens.

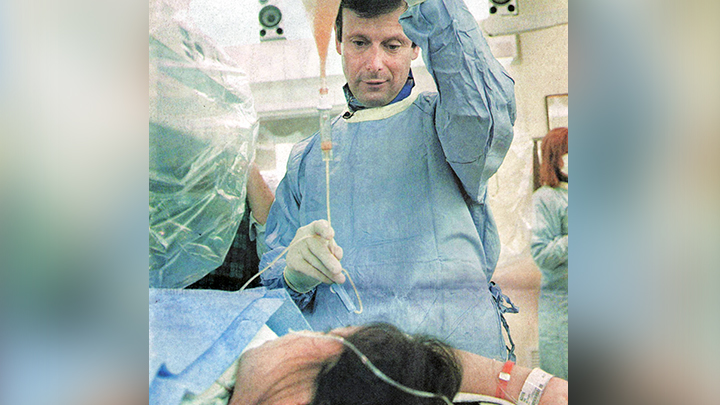

Dr. James Shapiro led the team which created the Edmonton Protocol for Type 1 diabetes 25 years ago. Supplied.

Francis Hesse lost his sight after Type 1 diabetes complications 30 years ago. Today, he’s insulin injection-free after receiving an islet transplant in 2024. Supplied.

Story by Su-Ling Goh

EDMONTON — Francis Hesse remembers hiding from his parents as a child, scared of the daily insulin injections he needed to avoid life-threatening blood sugar levels from his Type 1 diabetes.

“I hated needles.… I’d be hiding, mom and dad would be practically sitting on me giving me this needle,” laughs Hesse.

At age 59, he’s finally free of those injections after having an islet transplant in April of 2024. Islets are clusters of cells within the pancreas which produce insulin, a hormone which controls blood sugar levels.

“A month later and I was off insulin (injections) … it’s still hard to believe. Just amazing,” says Hesse.

The Grande Prairie man is among 330 patients who’ve received the life-changing procedure in Edmonton — today known as the Edmonton Protocol. The world’s largest islet transplant program, at the University of Alberta Hospital, celebrates its 25th anniversary this year.

Dr. James Shapiro led the team that developed the protocol in 1999. At the time, islet transplants had been attempted hundreds of times around the world, but few were successful.

“The Edmonton Protocol was designed as a ‘belts and braces’ last-ditch attempt to see if we could get islets to work,” says Shapiro, Canada Research Chair in Regenerative Medicine and Transplantation Surgery and Director of the Clinical Islet Transplant Program.

“We made radical changes to ensure sufficient islets were transplanted (by infusion into the liver), without the need for surgery. A special cocktail of anti-rejection drugs was designed to help the cells survive, eliminating the high-dose steroids used in all other transplant protocols at the time.… To our astonishment, it actually worked.”

After the first seven patients were successfully treated and the work was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2000, word spread quickly across the globe. Shapiro recalls receiving thousands of letters from desperate Type 1 diabetes patients and their families.

“It got a little chaotic. The hospital switchboard was choked for several days with patients and families asking how they could get on the (islet transplant) list,” adds Shapiro. “It was overwhelming.”

Since then, more than 2,500 patients have been treated with the Edmonton Protocol around the world, including 330 in Edmonton. These patients received a total of 781 transplants, and nearly 80 per cent were able to stop taking insulin injections for a median time of 95 days. As well, 61 per cent remained injection-free after one year, 32 per cent after five years, and eight per cent after 20 years. While most had to resume insulin therapy, the doses were usually much smaller than their original needs.

One of the challenges is patients’ need for anti-rejection drugs, which can have serious side effects. Senior Islet Specialist Douglas O’Gorman, who’s been working for the program for 24 years, says the procedure is evolving to reduce its dependence on pancreas donors.

“While we’re incredibly grateful to our (pancreas) donors, we’re limited by the number of donors available,” says O’Gorman. “And even from those donors, the islet isolation process itself only works about half the time where we have enough cells to get an effect in the recipient.”

Shapiro’s team continues to evolve the program, including working on using stem cells from a patient’s own blood, programmed to produce insulin, which would eliminate the need for donors and anti-rejection drugs.

O’Gorman says he and his colleagues are motivated by the patients they meet.

“You see them going through that journey and the challenges that Type 1 diabetes can bring,” he says. “It provides the motivation for you to … make a difference and have a positive impact in their lives.”

Hesse says his diabetes held him prisoner for nearly 60 years. Complications led to him losing his sight 30 years ago.

“I just couldn’t control (my blood sugar levels). It didn’t matter what I ate, how much I exercised, how much insulin I took — it was just terrible,” he adds.

Now that he no longer needs insulin injections, he’s able to leave his seniors facility for extended periods without a nurse, and truly enjoy time with his family.

“It’s pretty amazing what (Shapiro’s team has) done since day one until now, and getting better all the time,” says Hesse. “It’s incredible.”

For Shapiro and O’Gorman, ultimate success will mean treating all patients with diabetes, including children and people with Type 2.

“It would be fantastic for our work not to be needed by patients anymore,” says O’Gorman.

Shapiro adds: “We’re well on the journey to solving the next steps of the puzzle to one day make cell therapy a potential cure for diabetes.”