July 22, 2014

Story by Sharman Hnatiuk; photo by Stephen Wreakes

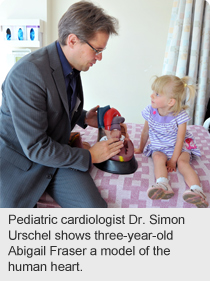

Abigail Fraser isn’t an average three-year-old.

At six months of age, the Airdrie girl made history when she became the first patient in Canada to receive an innovative anti-rejection therapy at Edmonton’s Stollery Children’s Hospital, without which she would never have been a suitable recipient for a heart transplant.

Today, Abigail is all smiles when playing with her older sister Hailey, but Abigail’s journey did not have an easy start. She was born with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), a rare congenital heart defect in which the aorta and left ventricle of the heart are severely underdeveloped and cannot pump blood properly.

The current standard of care for patients with HLHS involves three life-enhancing surgeries staged from within days of birth until age four.

The current standard of care for patients with HLHS involves three life-enhancing surgeries staged from within days of birth until age four.

Abigail’s parents, Nancy and Jamie, were familiar with the treatment option, having been through the surgeries with Hailey, who was also born with HLHS.

Abigail, however, experienced complications following her first surgery just days after birth. Her heart was too weak to undergo the second and third stages of the HLHS repair and she was transferred to the Stollery where she was assessed and listed for a heart transplant.

Unfortunately, Abigail’s immune system had developed antibodies to donor tissue used to repair her aorta during her first heart surgery. If a donor heart became available, her body would likely reject it immediately.

To help suppress her natural immune response, a team of doctors at the Stollery and University of Alberta developed a new immunosuppression protocol.

“We combined the cancer treatment drug Rituximab with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) to slow down her production of antibodies that would reject a donor organ while providing enough antibodies to fight off infection,” says pediatric cardiologist Dr. Simon Urschel, Clinical Director of Pediatric Cardiac Transplantation at the Stollery Children’s Hospital, and a researcher at the University of Alberta’s medical school.

“Together, the two therapies prevent the donor organ from being rejected.”

Abigail responded to the immunosuppressive therapy and, when a donor organ became available two months later, she was a suitable candidate for transplant.

“Pediatric organs don’t come available very often, so to hear your daughter would reject most organs was devastating,” says Nancy.

“We are so grateful to the team of doctors and researchers who made this treatment available so Abigail could accept a donor’s heart.”

The Stollery is the first and only academic health centre in Canada to successfully use the treatment in children in preparation for transplant.

Since Abigail’s transplant in December 2011, two other pediatric cardiac patients have successfully been transplanted following the Stollery anti-rejection therapy protocol.

“Abigail’s success is due to a collaborative team effort of researchers and physicians supported by her family,” says Dr. Lori West, a pediatric cardiologist at the Stollery Children’s Hospital and Director and Research Director at the Alberta Transplant Institute.

“Without research leading to the development of this protocol for children, this new therapy would not be available.”