January 16, 2015

Story by Greg Harris; photo by Paul Rotzinger

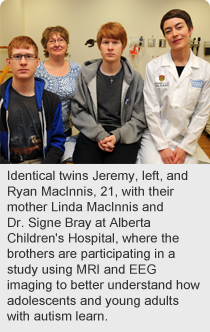

CALGARY — As a parent of twin boys with autism, Linda MacInnis knows full well the challenges of trying to navigate the system and find meaningful programming for her sons.

“It seems like the kids with autism are continually falling through the cracks, especially the older they get,” she says. So when she heard about a new research study at Alberta Children’s Hospital in Calgary that’s looking at how teens and young adults with autism learn, she was quick to sign the boys up.

A better understanding of brain function in people with autism could eventually help create more effective training and vocational programs for them, thus improving independence, employment opportunities and quality of life.

“I’m so glad someone is looking at this,” says MacInnis. “The only way the systems and supports will start to change is through studies like these. The more we know, the better off we’ll be as a society.”

“I’m so glad someone is looking at this,” says MacInnis. “The only way the systems and supports will start to change is through studies like these. The more we know, the better off we’ll be as a society.”

Researchers are using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and electroencephalography (EEG) to compare brain activity of 62 teens and young adults with autism and 62 without. The brain scans are taken while they’re engaged in computer tasks and while viewing pleasurable or unpleasurable images.

“In people with autism spectrum disorders, there may be some abnormalities in brain circuitry that contribute to differences in learning,” says Dr. Signe Bray, PhD, principal investigator in the study and a member of the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute.

“One of the theories is that the brain’s reward system — which is critical for facilitating learning — operates differently in people with autism,” says Dr. Bray, who is also an assistant professor of radiology in the Cumming School of Medicine at the University of Calgary.

About one child in 68 is diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. It is more common in boys than girls and there is no known cure. People with autism generally have difficulties with communication and social interaction. They can exhibit repetitive behaviours or show a preoccupation with specific subjects.

It remains unclear what the exact causes of autism are but scientists suspect there could be a number of risk factors, including genes, environmental effects, or early injury to the brain.

MacInnis’ sons Ryan and Jeremy, now 21, both struggled through the school system. They are currently working with the Ability Hub in Calgary, an organization dedicated to helping individuals and families with autism spectrum disorders.

“To me, they’re like normal teenage boys — they spend a lot of time playing video games and don’t much like doing their chores,” she says.

Researchers are currently looking for teens and young adults between the ages of 14 to 20. If eligible, they will undergo testing on three separate visits to Alberta Children’s Hospital, including an MRI and EEG.

For more information about the study, please phone 403-955-7440 or visit the website at http://www.asdbrainresearch.ca