February 22, 2022

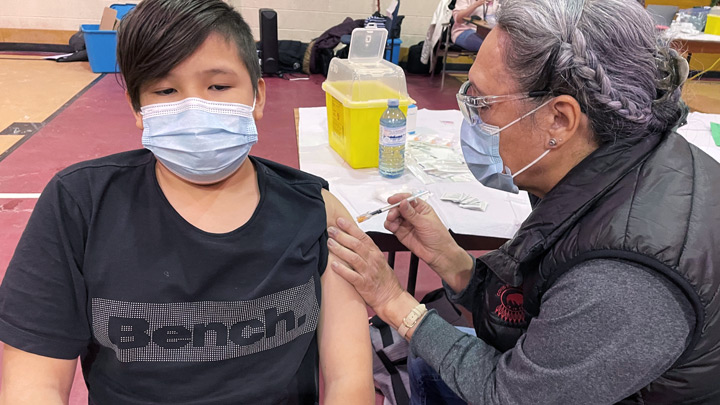

Eleven-year-old Kayson Creighton got his COVID-19 vaccination recently at a Sik-Ooh-Kotok Friendship Centre vaccine event in Lethbridge. At the centre, a big screen played movies for waiting families, adding to the festive atmosphere.

Participants in Chinook Regional Hospital’s Spirit of Art and Reconciliation (SOAR) program lit up when volunteers from the Salvation Army provided handmade gingerbread teepee kits.

Story by Sherri Gallant & Kelly Morris | Photos by Kelly Morris

LETHBRIDGE — In a global pandemic, the need to provide testing and immunization on a massive scale often means setting up services swiftly at a central location. But barriers such as transportation, language, poverty or cultural differences prevent access for many people, particularly among Indigenous and immigrant populations.

By travelling to meet at-risk populations where they are, South Zone teams are lowering these barriers and getting positive results to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

In partnership with community groups, this strategy has been successfully put into action by Stasha Donahue, senior advisor for Health Equity, Public and Primary Health Care in the South Zone, and her colleague Samantha First Charger, senior advisor, Indigenous Health for Alberta Health Services (AHS).

“We’ve been doing work like this with newcomers and diverse groups for a while, and we know that it works to meet people where they are,” says Donahue.

“So, in the early days of the pandemic we started a working group with a representative from the City of Lethbridge and a person with Sage Clan (a community patrol focused on helping the homeless and those suffering from addiction). We had weekly huddles during those intense periods to provide information about what the restrictions meant, and what the current status of infections was.”

As more community groups came aboard as partners, Donahue recruited a ‘coach’ from key organizations to serve as liaisons. Now, these Lethbridge Covid Community Coaches, along with public health inspectors Sean Robison and Stephen Kirkpatrick, ensure a knowledge transfer of accurate information.

“We started by inviting them to the table, to hear from them, and have them go back to their communities and share information,” adds Donahue. “We asked for their perspective as to what hesitancy about the vaccine was about. That local on-the-ground connection is so important — but the gap that was there before we started allowed the misinformation to start spreading.”

The homeless population was soon identified as a priority at-risk group, so public health began to offer immunization and swabbing at the shelter. When people who became ill had no place to isolate, a deal was struck with a local hotel to provide rooms where they could stay until they were well. Partner agencies brought food for them and, because the clients weren’t on the move while they recuperated, it was easier to provide support and connect them with relevant community resources.”

Donahue and First Charger realized people are wary of public health measures because of what they see as a top-down approach. “We should have started sooner, doing things with people rather than for them,” says Donahue. “Had we used some of the voices of our people rather than that top-down government voice, it would have been better. Because it was assumed that it was all political. And that misinformation spread faster than COVID did.

“If you know about what goes on in some of the countries where our newcomers fled from, you’ll understand why they might not trust government. Indigenous peoples' history, with colonization, carries the same sort of legacy.”

First Charger says she made it her mission for Indigenous peoples' programs to be Indigenous-led.

“My focus was giving the power back to the Indigenous community, making sure whatever we did was in a culturally-safe space, so people wouldn’t feel afraid. We broke jurisdictional barriers with these clinics.

“Before, we had AHS nurses going out to the communities to deliver the vaccines, but the reverse wasn’t happening. So, for the first time ever, the First Nation nurses were coming out to Lethbridge and delivering the vaccine. It was huge, a huge step.”

Soon, community engagement grew, she adds. Vaccine clinics were held at a park in downtown Lethbridge where people are known to gather. They were also held in shopping malls and in the parking lots of malls.

“We got the numbers up because we had Indigenous faces right there,” says First Charger. “We had a teepee up, we served food, we had music. We did something completely different. It didn’t look so clinical; it was warm, it was inviting, and Indigenous people recognized there were other people there — we were telling them that we were vaccinated, and we were OK. We sat on the grass with them. We didn’t rush anything. We offered drinks and said ‘let’s talk about it’. And we also said, ‘it’s OK to go and think about it’, because we’re gonna be back.”

Their effort to connect has extended beyond COVID-19 measures and also includes spiritual care and arts outreach in hospitals led by Indigenous staff, as well as a number of events in the downtown park.

Steps towards reconciliation have been taken — both in careful baby steps and in leaps. But there’s no question that even the smallest gestures can bring big meaning.

Earlier this winter, participants in Chinook Regional Hospital’s (CRH) Spirit of Art and Reconciliation (SOAR) program lit up when volunteers from the Salvation Army provided handmade gingerbread teepee kits, both for those who could attend the weekly session and those who couldn’t. SOAR is a recreation therapy program offered to Indigenous inpatients. Activities provide entertainment, distraction and cultural connection.

“It’s really nice for those patients to have something to do while they’re in here — it takes their mind off some of their illness. It’s health-promoting,” says Roxie Vaile, Indigenous hospital liaison.

“I think sometimes the reconciliation piece can be really overwhelming, but when it comes down to our own community and people just getting together — it can make a big difference.”

CRH has a purpose-built ceremony room, known as the Golden Eagle Lodge, which can accommodate smudging — an important Indigenous ceremony where medicinal herbs are burned for purification and prayer. For Indigenous patients who lost their culture due to residential schools, the ceremony reconnects them with their traditions. For some patients, the opportunity to smudge is new, and Indigenous Health staff are there to guide them through the process. Making that connection often opens a dialogue that reveals areas where liaison workers, like Vaile, can guide them to more community supports.

First Charger points to that same power of Indigenous-led connections in her work with Donahue outside the hospital and with other populations. Newcomers in Lethbridge, including the largest population of Bhutanese refugees in Canada, have continued to benefit from this approach.

“There are so many learnings,” says Donahue. “These relationships are so important, anytime, but particularly in the time of a pandemic.”