October 11, 2012

Story and Photo by Greg Kennedy

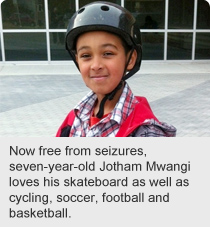

One year ago, life was a lot more frustrating for seven-year-old Jotham Mwangi.

The Edmonton boy was blanking out dozens of times a day. Falling off his skateboard. Tumbling off his bicycle. Missing key bits and pieces in the classroom. Mistaken at first for daydreaming, his behaviour turned out to be the result of epilepsy.

“Jotham would look like he was daydreaming,” says mother Chantelle Minor. “He’d be riding his bike and he’d fall off, and he wouldn’t remember how he fell off. Sometimes he’d lose bladder control. I noticed he was having a hard time with academics like reading and counting. He would shake or bite his lip. I got tired of waiting to see specialists. I took Jotham to the Stollery Children’s Hospital emergency department and, within three days, he was in the clinic.”

Edmonton-area children with epilepsy are now receiving diagnosis and treatment within days thanks to a new Alberta Health Services (AHS) clinic that provides them with specialized care when they visit the Stollery emergency department (ED).

The Pediatric Emergency Seizure Clinic addresses the needs of families who bring their children to emergency with first-time seizure, febrile (fever) seizures and new-onset epilepsy. ED medical staff provides the family with an information package and makes an appointment on the spot for the family to return within seven to 10 days to the new clinic for comprehensive care.

At the seizure clinic, an EEG (a test that measures and records the electrical activity of the brain) was performed on Jotham, who was diagnosed with childhood absence epilepsy, which results in brief but frequent seizures. The Grade 3 student was experiencing 30 or more seizures a day, each lasting 10 to 30 seconds or more.

“Now he’s on medication,” says Minor. “He’s been seizure-free for a year. I thought it was amazing. It was great. It was quick. It’s helped tremendously. It’s helped him to learn. I’ve noticed improvement in his speech, his activity level, his schoolwork, everything.”

A typical wait in pediatric neurology to be seen for epilepsy is six to nine months, according to nurse practitioner Laura Jurasek, who oversees the new clinic.

“For children who are having ongoing seizures, that can be very debilitating and disruptive in their life,” Jurasek says. “It’s important to get seizures controlled early. It becomes a big safety issue for kids on high playground equipment, swimming or riding a bike, or anything like that, when they blank out. It also becomes a big issue for learning. At school, they’re missing a lot of instruction time with teachers.”

The clinic, established last year at the Stollery, has helped more than 200 children to date and sees about five new patients a week.

Clinics such as the Pediatric Emergency Seizure Clinic also reflect the growing role of nurse practitioners at AHS. They are highly qualified nurse specialists who are able to diagnose, order tests, prescribe treatment and medication as they manage independent clinics and carry their own patient caseload.

“I like that it’s groundbreaking,” Jurasek says of her clinic. “You’re a pioneer in a new role that’s amazingly beneficial to the health care system.”

She also manages her own patient population from referrals to pediatric neurology at the Stollery and manages an Adolescent Epilepsy Transition Clinic that helps up to 10 young patients a month make the often-stressful change to the adult epilepsy program. As well, she’s part of the Comprehensive Epilepsy Program offering surgical options for intractable seizures, and an interdisciplinary team that conducts the Ketogenic Diet Program, which prescribes a high-fat, low-carb diet to control seizures for kids who may not respond to medication.

“Many of these children who have repeated seizures are coming to the emergency department,” Jurasek says. “It’s better if you can see them early, treat them early and educate families about when they need to seek help — and then get them on medication to prevent their seizures. As well, instead of their family having to come to emergency, my patients can call me.”