October 23, 2012

When John and Kerry Minchin asked their five-year-old son David how he felt about being the first person to try a new procedure to fix his heart, he answered without hesitation.

“Sure,” the boy said, “anything for Dr. Coe.”

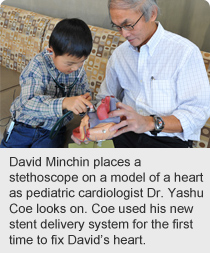

Stollery Children’s Hospital pediatric cardiologist Dr. Yashu Coe has pioneered a new system for opening narrowing or blocked blood vessels that could revolutionize how this common procedure is performed around the world.

Stollery Children’s Hospital pediatric cardiologist Dr. Yashu Coe has pioneered a new system for opening narrowing or blocked blood vessels that could revolutionize how this common procedure is performed around the world.

Coe’s ‘all-in-one’ stent delivery system was used for the first time to open David’s left pulmonary artery. The procedure was a success; the new delivery system performing as expected.

“I would say that David’s energy has increased about 30 per cent, he’s running around full throttle and Dr. Coe said it may increase,” says John Minchin. “Our family is grateful to Dr. Coe. He is going to push to provide the best for his patients.”

Stents are wire mesh tubes that can be permanently placed into a narrowed vein or artery to hold it open. Stent placement is done by a cardiologist who puts a catheter into the body through the femoral artery or vein in the groin, and threads it up to the area that has narrowed.

This procedure typically takes two to four hours and is performed about 40 to 50 times annually in children in the Edmonton Zone of Alberta Health Services.

“One in 100 children is born with a heart defect,” says Coe. “Stent placement by catheter for treatment of congenital heart defects such as narrow blood vessels including the aorta is a standard treatment for children born with these defects.”

Coe’s stent delivery system is designed to provide better precision and control when moving the catheter through the body and into the heart. It also eliminates several steps required when using the conventional method. As a result, procedures are expected to be performed in less time, reducing the risk of complications.

“In the old system, getting the stent to where you want to place it can be difficult as you pass through the heart. Then deploying the stent exactly where you want it may take a while, which adds to the procedure time in as many as one-quarter of my cases,” says Coe.

“These patients are already sick and have compromised cardiac function, so if we need to open an artery, it’s best to get in and out of the heart as quickly as possible. This also means patients should be under anesthetic for less time, which is beneficial because anesthesia can depress heart function.”

Over the past three years, Coe has been working on the new delivery system with NuMED Inc., a worldwide leader in pediatric cardiovascular medical products. Coe obtained approval from Health Canada to test his final design in a clinical setting on David, who had been diagnosed with Tetralogy of Fallot, more commonly known as blue baby syndrome, which causes low oxygenation of the blood.

Coe says he will continue to test the new delivery system on more pediatric patients before submission to health regulatory authorities for approval.

“I can see this phasing out the conventional method, and this new stent-delivery system becoming the standard protocol both domestically as well as internationally to treat cardiac defects and perhaps coronary artery disease,” says Coe.

“The new design has applications for pediatric as well as adult patients, and could be modified for safer stent delivery in other parts of the body.”