December 20, 2012

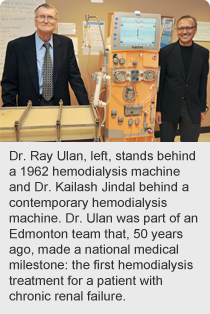

Story by Sharman Hnatiuk; photo by Stephen Wreakes

Dr. Ray Ulan knew it was a revolutionary device as soon as he saw it.

‘It’ was a Teflon shunt, developed in Seattle in the early 1960s, that could be surgically implanted and allow for repeated access to a blood vessel, making long-term hemodialysis possible for patients with chronic renal failure.

“That was a game-changer,” says Dr. Ulan, who was a medical resident when he and a team of Edmonton-based technicians and clinicians (including the late Dr. Lionel MacLeod, Director of Endocrinology and Metabolism at University of Alberta Hospital), visited Dr. Belding Scribner and the Artificial Kidney Program in Seattle, where treatment for patients with chronic renal failure was started in 1960.

“That was a game-changer,” says Dr. Ulan, who was a medical resident when he and a team of Edmonton-based technicians and clinicians (including the late Dr. Lionel MacLeod, Director of Endocrinology and Metabolism at University of Alberta Hospital), visited Dr. Belding Scribner and the Artificial Kidney Program in Seattle, where treatment for patients with chronic renal failure was started in 1960.

Excited about the shunt and the success of the Seattle program, the Edmonton team worked toward establishing a hemodialysis program here. And on Dec. 21, 1962, a 17-year-old girl made Canadian history at University of Alberta Hospital by becoming the first person in the country to undergo hemodialysis for treatment of chronic renal failure.

Before then, there were no treatment options for patients in chronic renal failure in Canada; only acute dialysis was available for patients with short-term renal failure and this temporary treatment could last no more than a few weeks. Life expectancy for people with chronic renal failure varied depending on the level of kidney function remaining for each patient; however, once the kidneys failed, patient death was imminent. Canada’s first hemodialysis treatment for chronic renal failure extended the patient’s life by five years.

“When we started, we didn’t know how the body would adapt to dialysis,” recalls Ulan, on the eve of the 50th anniversary of this national medical milestone. “But after the first year of the program, we saw a rise in the number of patients. After a while, it was clear dialysis worked.”

Today, the Northern Alberta Renal Program provides services for more than 1,100 renal patients on dialysis at 22 sites through central and northern Alberta.

In 1962, the treatment was still considered experimental.

“We couldn’t experiment in the traditional way of one group gets treatment, one doesn’t, because if people didn’t get the treatment, they died. Survival was the measurement,” says Dr. Ulan.

“We knew this treatment was going to be significant but we never predicted the way the whole thing evolved; the fact that other treatments, like transplant or peritoneal dialysis, would spin out as treatment options for chronic renal patients.”

Chronic intermittent hemodialysis is a method of blood purification where blood from a patient with kidney failure is passed through a membrane-containing device called a dialyzer which removes retained toxins and excess fluid. Patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis typically are connected with blood lines from a blood access site to the dialyzer for four hours, three times per week. Peritoneal dialysis uses a membrane in the abdomen.

Dialysis options for patients include conventional daytime dialysis, home hemodialysis, nocturnal dialysis at the hospital, and peritoneal dialysis.

“When you look at the size of the dialyzers on the unit today, and the different dialysis options for patients, you can see how far this program has come to improve access and outcomes for patients,” says Dr. Ulan.

The need for this service continues to rise. Nearly 38,000 Canadians were living with kidney failure in 2009 — more than triple the number (11,000) living with the disease in 1990.

These patients include Wayne Gaalaas. In 1970, the Camrose man became the first patient in Alberta trained and discharged for home hemodialysis treatment.

“When I started on dialysis in 1967, I would have to drive to the U of A hospital three times a week for a 12-hour session and then drive home and go to work,” says Gaalaas.

“Home hemodialysis gave me back a lot of time and freedom, and kept me alive for another eight years. That’s when my sister donated a kidney for my transplant in 1978.”

The University Hospital Foundation has supported NARP since 1988, helping the program to stay on the leading edge of kidney treatment by supporting the purchase of the most advanced dialysis technology. Most recently, the foundation matched a $1-million donation by the Matt and Betty-Jean Baldwin Foundation. The $2-million gift will allow the program to purchase 45 additional home hemodialysis machines and the related supplies. The investment will allow more end-stage kidney disease patients to receive superior dialysis therapy in the comfort of their own homes.