May 6, 2013

Story by Greg Kennedy; photo by Amber Bracken

When Cynthia Gibeau came to hospital with difficulty breathing and a chest full of “strange whistling sounds,” she wasn’t sure what to expect.

When doctors at Edmonton’s Mazankowski Alberta Heart Institute diagnosed multiple blockages in all her major coronary arteries — and advised open-heart surgery — the mother of five feared the worst.

When doctors at Edmonton’s Mazankowski Alberta Heart Institute diagnosed multiple blockages in all her major coronary arteries — and advised open-heart surgery — the mother of five feared the worst.

But after more consultation, her fear turned to joy when the interventional cardiology team at the Mazankowski presented the 57-year-old with a new, non-invasive option that could see her go home the next day.

Younger heart patients like Gibeau, with narrowing or blocked arteries, can now benefit from a revolutionary device that restores blood flow and then dissolves into the body over time.

The Mazankowski Alberta Heart Institute is the first and only medical centre in Western Canada now using the Absorb bioresorbable vascular scaffold (BVS), a first-of-its-kind device for the treatment of coronary artery disease. This technology — made by global health care company Abbott — was made available on a special-access basis authorized by Health Canada.

“Once they said that that could be done, the whole weight of the world lifted off,” says husband Jack Gibeau. “It was amazing that option was there, and it’s a non-invasive surgery. Who wouldn’t want that?”

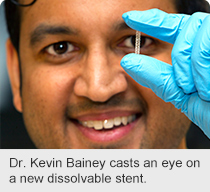

Dr. Kevin Bainey, an interventional cardiologist and specialist in clearing blocked arteries for Alberta Health Services (AHS), says: “This bioresorbable stent disappears over time, leaving patients with an artery that has the potential to naturally flex, expand and contract as needed to increase the flow of blood to the heart in response to normal activities such as exercise.”

During an angioplasty procedure, a stent is inserted into an artery using a catheter, a thin plastic tube. A typical stent is a tiny wire mesh tube made of metal that opens a clogged artery, improving blood flow. The new Absorb stent is made of polylactide, a material often used in dissolvable sutures. This allows the stent to gradually dissolve over one or two years, leaving a strengthened artery that can stay open on its own.

The dissolvable stent does not replace the traditional metal stent in all cases, but can offer advantages when treating certain cardiac patients under the age of 65.

“For our younger patients, the best option is not to leave a metal stent behind,” says Dr. Robert Welsh, Director of the Cardiac Catheterization Lab at the Mazankowski Alberta Heart Institute.

“Let’s say a 40-year-old has a heart attack or needs an angioplasty. We know the patient will most likely be back in five or 10 years, and may even need a bypass in the future. The lack of metal may actually make their ongoing care much better. This new bioresorbable scaffold technology may actually help to protect people long-term.”

In Gibeau’s case, doctors initially considered Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) surgery. This open-heart surgery uses a section of an artery from elsewhere in the body and bypasses a blockage in a coronary artery to improve blood flow.

But performing a bypass on a patient this young could create challenges should a second bypass operation become necessary later on. Similarly, putting in a permanent metal stent now could also make it more difficult to perform a first bypass, should her condition worsen.

“With advances in interventional cardiology, we are now able to treat multiple blockages with stents; hence avoiding open heart surgery. We are fortunate to have these dissolving stents which help preserve the opportunity for CABG surgery in the future if required,” says Dr. Bainey.

“For Cynthia, I placed multiple stents in all her major coronary arteries — but placed a special Absorb stent in a major artery which may allow her to have a bypass in the future, should she require one due to the progression of her coronary artery disease.”

Gibeau spent only one night in hospital with complete recovery, compared to seven to 10 days for a bypass patient.

“It was like a miracle to me not to have open-heart surgery,” says Gibeau, a caterer who celebrated her 36th wedding anniversary on April 30.

“Now I can take deep breaths,” adds Gibeau. “I can walk a little faster. I can keep up with everybody now. I have a lot more energy. The care was wonderful.”